In-between working on the Elfe S3 I’m also still working to get my Diana 4 ready. It has been sitting in my workshop for a while, waiting for me to finish it.

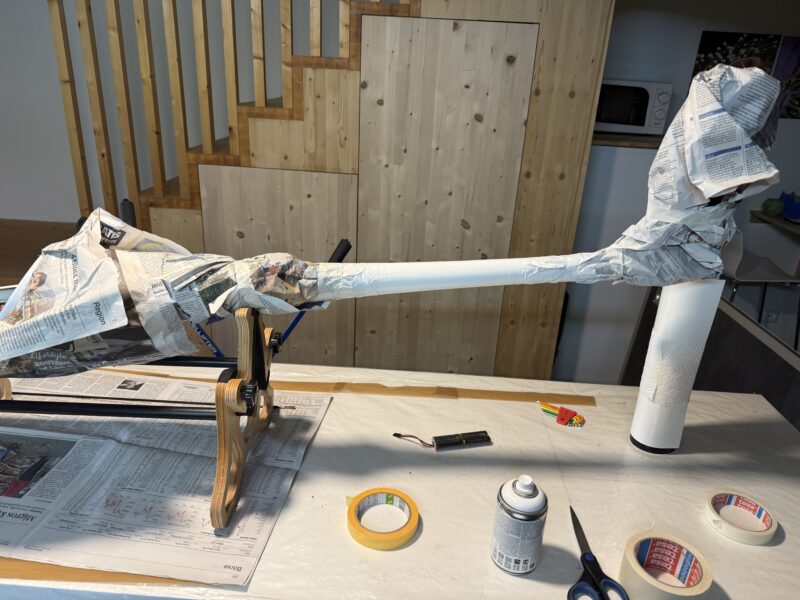

Fitting the canopy frame is always a bit of a pain and I usually leave it to a day where I feel like having a go at it.With a self-built canopy frame and canopy there are no real shortcuts. It’s a job that requires a lot of time and patience.

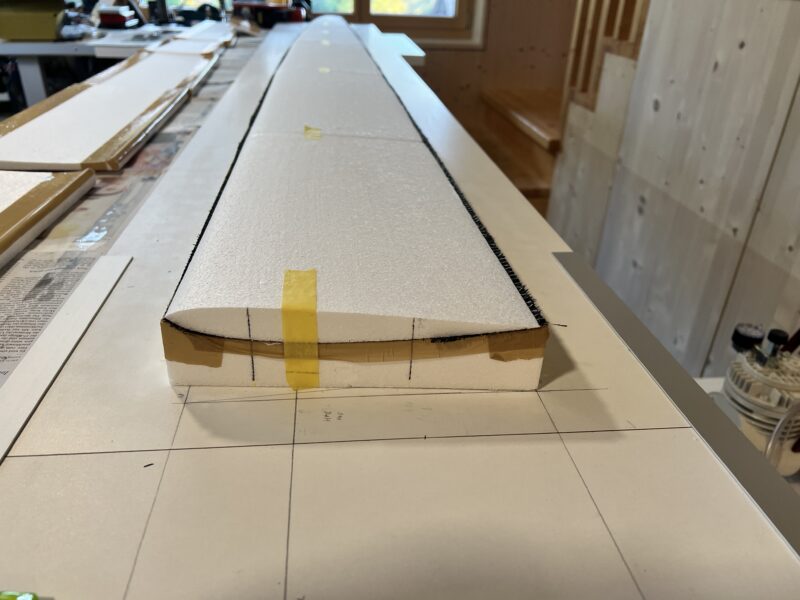

Essential is that the canopy frame is sanded back so that the canopy nicely fits onto it and is level (or just a bit inwards) from the fuselage. The worst looking canopies are those that stand outside the fuselage.

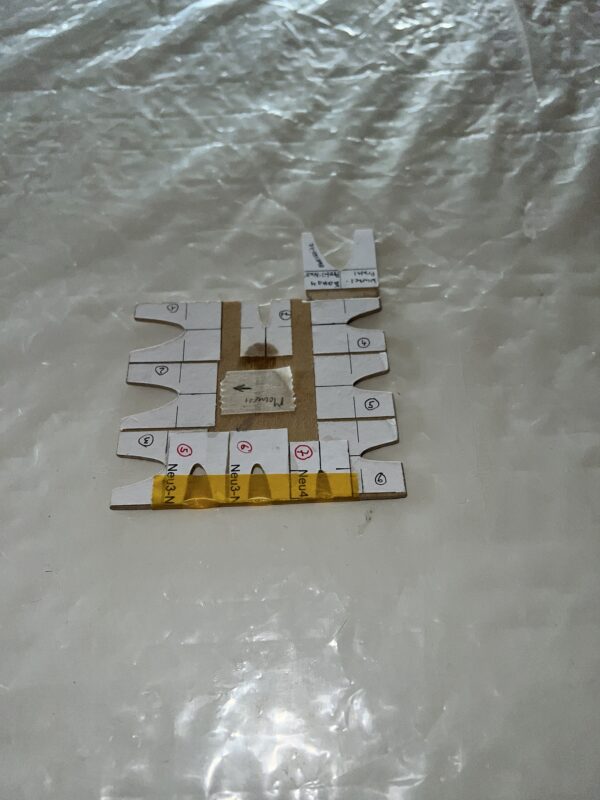

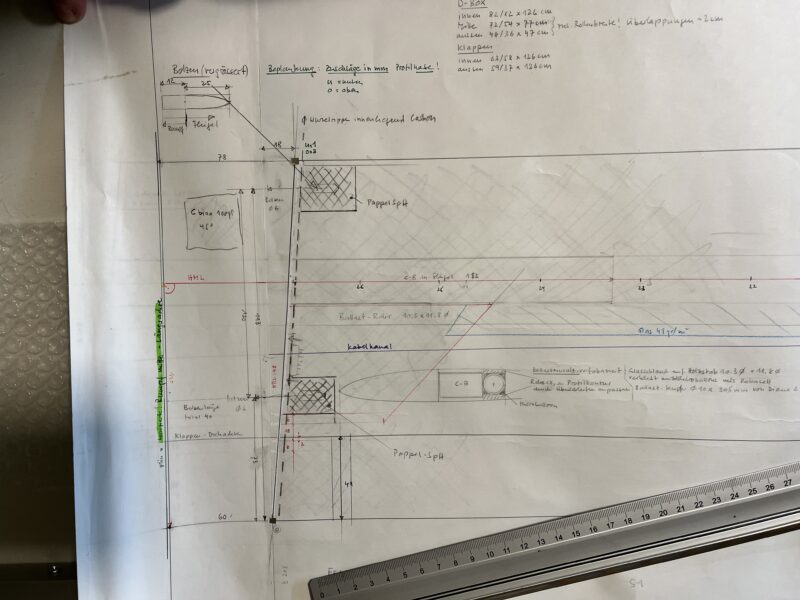

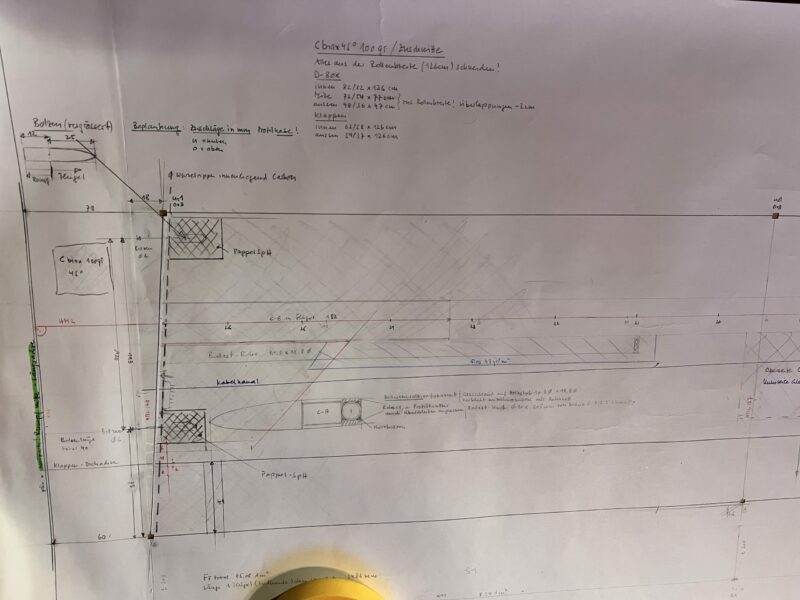

Once the frame is sufficiently sanded back, it’s time to cut the canopy to size. I usually do a rough large cut and then try it on, marking it with a marker pen and further cutting it back (I have a nice Tamiya canopy scissors that does a great job). Once you more or less have the right shape, it’s time to make the perfect fit. Before you do so, make sure that you mark the center line front and rear of the canopy so that you always put it in the exact same place. I then use a permagrit sanding block (the really coarse one) to slowly sand back the edges of the canopy. And then just try, sand, try, sand, etc…. It usually takes me at least a few hours to get it right. Once you’re satisfied with the fit I use a fine grit sandpaper to smoothen the edges of the canopy.

Before glueing the canopy to the frame I first make sure that the fuselage is nicely waxed so that the canopy doesn’t glue to the fuselage, but just to the frame (epoxy always has a way of “escaping”).

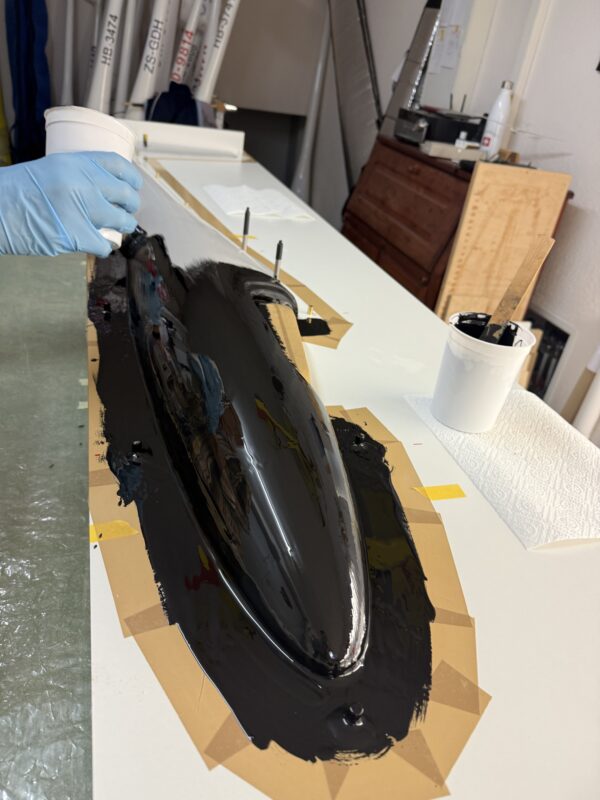

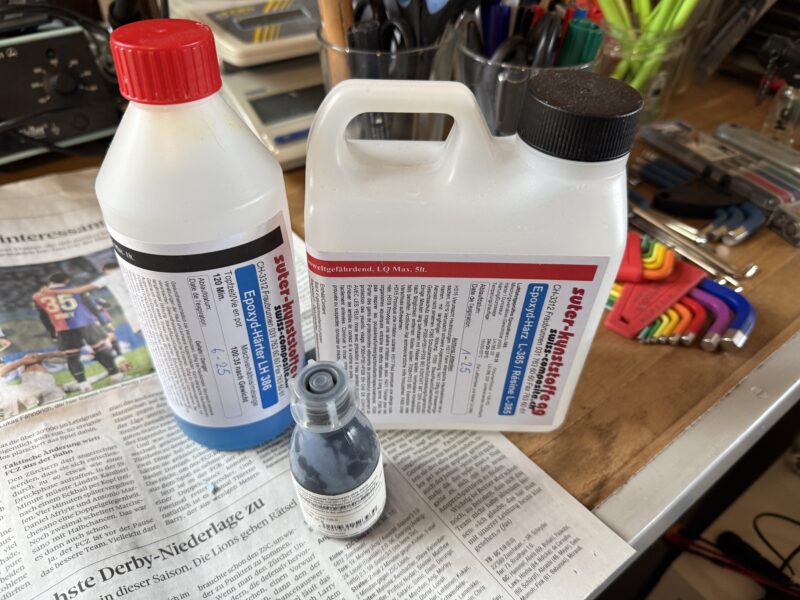

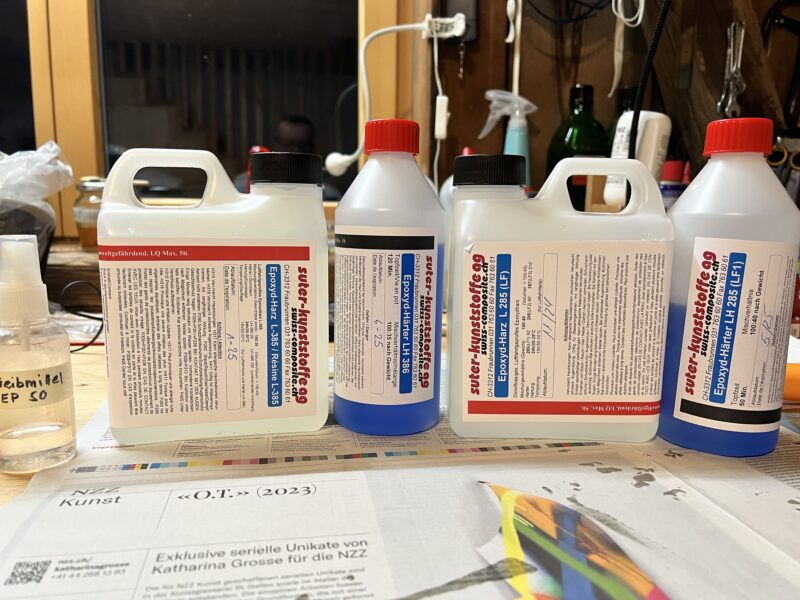

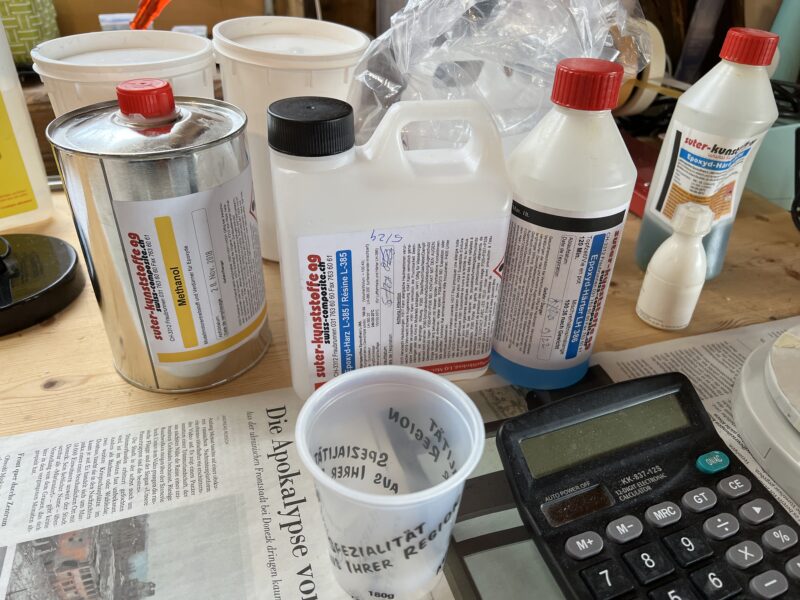

Not it’s time to glue it on. I use normal epoxy resin, coloured grey (same colour as my canopy frame) and thickened using both micro-balloons and aerosil. Using a pencil I apply it evenly around the frame and place the frame on the fuselage. This is probably the hardest part – too much and you have a mess with epoxy coming out when you place the canopy, too little and you have gaps between the frame and the canopy.

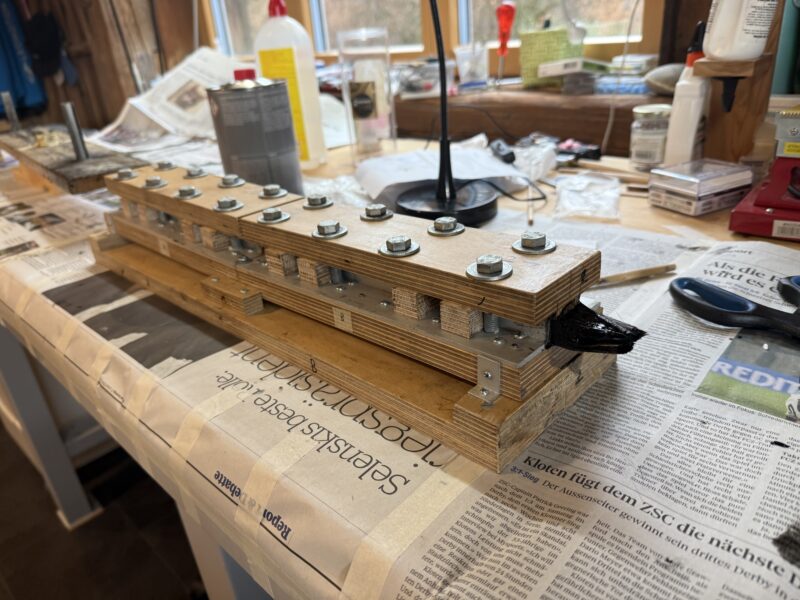

I then carefully position the canopy onto the frame. Make sure you remove any excess epoxy – if there’s some on the edge of the canopy then use some alcohol to make sure that the canopy is clean (saves a lot of work when spraying the canopy edges). If you did your job fitting the canopy really well, it fits perfectly and you can just let it cure. I’ve never succeeded in doing that. So I usually end up positioning the canopy with bits of tape or double-sided tape on ebechi. You can also wait for the epoxy to partially cure and then carefully press the canopy onto the frame in places where the canopy stands out. Then let the epoxy fully cure.

I got lucky and the fit turned out very well. I did have to fill a few gaps between the canopy frame and the canopy with some thickened epoxy, just to make sure that the inside edge is perfect.

Once all this is done I carefully sanded the edges of the canopy so that they are nice and smooth. I also lightly sanded the edge of the canopy to be spray painted. Then I carefully covered the bits that are not to be painted (make sure you use good masking tape, not the 3m DIY stuff!) and first applied a bit of primer, followed by a few coats of white. I’m pretty satisfied with the result.

You must be logged in to post a comment.